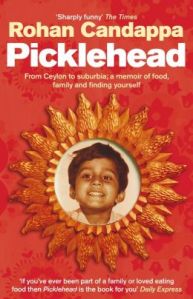

Rohan Candappa’s entertaining food memoir with recipes, Picklehead: From Ceylon to Suburbia; a Memoir of Food, Family and Finding Yourself, is an engaging way to learn about the experience of growing up as the child of immigrants in 1960s and 70s London. My oldest daughter, in her wisdom, has coined a term to express her own similar experience: “half-immigrant,” and it is that concept that gives the title to today’s blog post.

The memoir is split into two distinct narrative modes: the primary one is a retrospective look at how Candappa finds himself buying a can of korma sauce at the supermarket so he can feed his hungry children quickly when he grew up eating delicious homemade Indian food at home. The second part, which I find to be the most fun to teach, is made up of a series of half-chapters chronicling “A Brief History of Curry in England.” This section is divided into five distinct parts, interspersed throughout the autobiographical narrative. When I assign this book in class, I tend to assign those chapters to be read together as a unit first, because I have found that otherwise undergraduates really feel thrown off by the sudden intrusion of a different discourse in a book they thought they’d figured out already.

Although this structure might seem direct enough, if a bit quirky, the tale that unfolds from between the book’s covers is layered very thickly: readers get three life stories–Candappa’s own, his mother’s and his late father’s–all rolled into one account of a middle aged man coming to terms with his ethnic/racial heritage and the culinary choices he faces as he decides how best to convey this patrimony to his own offspring. The introduction sets up the themes that organize the rest of the text that follows:

If you’re the child of immigrant parents, the food you eat at home is more than just the food you eat at home. It is a link to the world your parents came from. It has echoes of past places, past peoples, and past events. It is a conduit of both family history and history in a far wider sense. (10)

So part of Candappa’s purpose in writing is to bear witness to this condition of what Marianne Hirsch calls, “post-memory,” or the memory that people at a remove from trauma, in this case the child of immigrant parents, have of the original traumatic event as it has been conveyed to them by the generation that experienced it. In Candappa’s text, that full-blown experience of the trauma of his parents’ individual stories of displacement and the violence they witnessed as young people growing up in the waning days of the British Empire, still unsettles the British-born writer. The cycle stops with his children, however, much in the same way that the culinary tradition stopped with Candappa himself. As he confesses, in choosing the time savings and convenience of canned korma sauce over the more labor intensive home-made curry in the style that his own parents prepared, Candappa knows he’s foregoing an opportunity to communicate a sense of his own culinary patrimony to his own children, who are no longer defined by the grandparents’ experience of immigration in the same way Candappa and his brother were by their parents’:

Twenty-four minutes versus two hours when you live in a cash-rich but time-poor world really is a bit of a no-brainer. But as I chopped the chicken breast fillets into pieces, fried them in a pan and poured the sauce over them, I knew that, on some intangibly unsettling level, it was a no-culturer too. (10)

Picklehead is a unique meditation on a particular aspect of the life experience of what’s come to be known as the “sandwich generation,” those adults who care for their aging parents as the same time as they are still raising their dependent children. While Candappa’s mother appears to be very independent and carrying out an active and enriching life filled with meaningful work at the time when Candappa published his account, his father had already died. By calling attention to his circumstance of being the adult “child of immigrant parents” and also the parent of thoroughly British children, Candappa suggests that he is caught in the middle as the caretaker of one type of memory–the collective family memory of a colonial life that preceeded their arrival on British shores, and the main architect of his children’s absolutely modern life, unmarked in many ways by outward expressions of racial or ethnic consciousness or prejudice thanks to his own success as a provider, and to the flattening effect of the hectic pace of contemporary life, which demands quick and easy access to uniformly processed food, whatever its origins. After all, as Candappa took stock of how estranged he had become from his heritage, he realizes that his country has become enthralled by the very food that once marked him as a racial outcast in the school cafeteria of his youth: curry. The rich and rewarding (and side-splittingly funny) memoir he produces, then, is a successful attempt to come to terms with the fundamental question: “what, if any, was the link between what I had lost and what the country had gained?” (11).